My Heart Is a Prayer

Ryan Row

hey make my heart out of stone. A slate-colored hunk of granite run through with thin veins of fool’s gold like silver cracks that the father found in the mountains outside of town. He had been gathering lackweed to chew so that he could make himself numb and could fall asleep in the meadows in nests of dry grass like a bird. The afternoon sun burned his skin, and he felt almost as if the light were passing through him. He felt like a window. Like a single pane of a glass.

hey make my heart out of stone. A slate-colored hunk of granite run through with thin veins of fool’s gold like silver cracks that the father found in the mountains outside of town. He had been gathering lackweed to chew so that he could make himself numb and could fall asleep in the meadows in nests of dry grass like a bird. The afternoon sun burned his skin, and he felt almost as if the light were passing through him. He felt like a window. Like a single pane of a glass.

He couldn’t sleep at home anymore. The old feather bed was too soft. The mother slept turned away from him, and the curve of her neck in the blue moonlight looked to him like a hooked knife. The silence there had a body and a mouth, and he could feel, always, its teeth against his neck. Silence was a vampire.

He had broken their clock weeks ago with a fire poker. Back then, the ticking noise had hurt him somehow. Now it was the silence.

When he first saw the stone he was rising from a dream in which the moon was his heart and the sun was his mind. His teeth ached and were stained black from the lackweed, which tasted almost the same as licorice. The stone, from his low angle, was like a mountain poking out of the grass. Still thick-headed with lackweed, his mind and heart spinning like divine bodies, he began thinking on what, exactly, made a heart beat.

he mother whispers to my heart for hours. She cradles the stone in a small room at the back of their lab while sunlight strains through a small window, and tallow candles burn, and fits of black smoke spin above her in the amber light like the insubstantial bodies of angels or demons. She tells my heart all of her sins and hopes. Her skin seems brittle and yellow like fine, aged paper, and I worry that even the soft fingers of the prayer smoke may damage her. The first stage the ritual, they have decided together, is confession.

he mother whispers to my heart for hours. She cradles the stone in a small room at the back of their lab while sunlight strains through a small window, and tallow candles burn, and fits of black smoke spin above her in the amber light like the insubstantial bodies of angels or demons. She tells my heart all of her sins and hopes. Her skin seems brittle and yellow like fine, aged paper, and I worry that even the soft fingers of the prayer smoke may damage her. The first stage the ritual, they have decided together, is confession.

“I have never,” she says, stroking a silver vein of pyrite in my heart, “loved anything more.”

Her words braid together with the threads of smoke and disappear in the light.

ogether, they soak my heart in seawater thick with violet flower petals and crushed sage. They boil my heart in calf’s blood and vinegar. They cut it into a perfect sphere and bless it under the full, blue moon, surrounded by an array of mirrors designed to capture the light. The night is wild, and I can hear ancient chanting from across the mountains. The stars sing in silence. The mother makes exact notes on the quality of the light and on the degree of the moon on a length of lambskin while the father performs the blessing.

ogether, they soak my heart in seawater thick with violet flower petals and crushed sage. They boil my heart in calf’s blood and vinegar. They cut it into a perfect sphere and bless it under the full, blue moon, surrounded by an array of mirrors designed to capture the light. The night is wild, and I can hear ancient chanting from across the mountains. The stars sing in silence. The mother makes exact notes on the quality of the light and on the degree of the moon on a length of lambskin while the father performs the blessing.

The father dances naked with fistfuls of red flowers. He dances around my heart and the mirror labyrinth in the center of a dodecagram drawn exactly in salt and iron dust. He feels wild. He hears, without hearing, the song of the stars. He breathes heavily and sweats into the earth. His lungs feel like the famous hot air balloons of the coastal cities. His blood is expanding inside his body. He eyes the mother. Her skin is whiter and more terrifying than bone.

“You may stop,” she says, making a final series of notations with quick, sharp motions. At last she looks up and meets his stare. The father has the sensation of looking through a telescope and observing the lifeless surfaces of dark planets very far away as he did once when he was a student and he visited the Louren observatory on campus.

“The moon is past its apex,” the mother continues. “Watch, the mirror lattice is clouding over. The mirrors will break. This is enough.”

The father breathes with effort. The air feels thick and heavy, and he watches the mirrors lose their shine like blinded eyes. Like clouds over the moon. His skin starts to feel cold.

y heart is a prayer. My heart is a temple, is a church to an absent god. Is an egg for all the misery of the universe.

They carve the black runes into one hemisphere of my heart and the celestial runes into the other. They barely understand these lost letters and they argue over their order and placement. They are only capable of reading the first meaning of each character. Life. Soul. Heaven. Darkness. Eternity. But I understand.

Order is irrelevant.

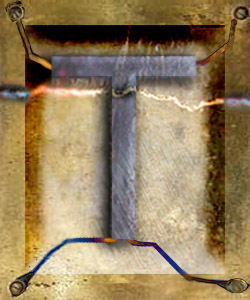

Lastly, they place my heart in a thick glass enclosure rimmed with copper. They fill the enclosure, my ribcage, my heart-cage, with a clear alcohol floating with flecks of gold and droplets of quicksilver. They weld it shut with mathematically calculated chemical ignitions along the copper seams. White lines and spitting sparks. The mother thinks she sees my heart beating through the tiny window, very very slowly. The father believes it is glowing faintly.

Both are right.

hey are second rate alchemists at best. They have a small shop and lab outside the mountain city of Zaren. They make their money mixing potions and portioning out measurements of herbs and powders for head colds and stomach aches, like apothecaries. They perform simple heart sync procedures wherein they find a patient’s pulse and align it with their own as a method of therapy, which they invented. It is based on a procedure that turns weak-willed subjects into slaves, but they have not used it this way since they studied it at university. Sometimes they test and certify the strength or flexibility of new alloys or acids or they research in specific areas for the city government, such as the validity of old magics as it relates to the police force of the city.

hey are second rate alchemists at best. They have a small shop and lab outside the mountain city of Zaren. They make their money mixing potions and portioning out measurements of herbs and powders for head colds and stomach aches, like apothecaries. They perform simple heart sync procedures wherein they find a patient’s pulse and align it with their own as a method of therapy, which they invented. It is based on a procedure that turns weak-willed subjects into slaves, but they have not used it this way since they studied it at university. Sometimes they test and certify the strength or flexibility of new alloys or acids or they research in specific areas for the city government, such as the validity of old magics as it relates to the police force of the city.

They are small time and they have not done any true alchemic calculations or research since they were both children themselves studying for their certifications. Now they are up all night again. Now they scour the city for ancient texts and freshly minted research papers in from the capital. They write each other notes in mathematical notation on stone slabs and scraps of animal skin. They think in strings of loose logic and arcane rumor. The father is turning forty and he thinks he sees death in the shadow of the sun. The mother is forty-one but she feels much older.

Chalk hangs in the candlelight of their home like the presence of a ghost. They study the old ways and the new under the ever weight of this presence.

The flow of arcane energies like the flow of blood in a body. The theory of soul. The theory of body. The witch’s ritual. The geomancer’s golem. The necromancer’s law. They are building an exquisite corpse of theory and practice. The theory of death.

They are not visionaries nor geniuses but they are intelligent and well trained, though rusty. They have a passion that has crossed the invisible line drawn within the mind, and both have entered into the land of the insane.

They chemically weld together my skeleton with tiny pinches of white hot light. The father has burned off his fingerprints in this way. I am to be made of copper, because copper can conduct lightning and is capable of absorbing an ancient blood blessing. They carefully measure and file down the teeth of copper gears and fit them together at my joints. They give me hands, huge over-sized metal hands. With these I could crush stones. The gears inside are too delicate to be made any smaller. They give me a head, a featureless male bust, and glass eyes, even though, according to their calculations, I will see with my heart. The copper network of my skeleton connects my heart-cage to the clockwork mechanisms of my body like a petrified vascular network.

I wish I could help them. Could speak to them in their sleep. Stroke their cheeks and hair and tell them everything is all right. Keep going. You are almost there.

As it is, they are barely managing.

t night, when their spines are stiff and their vision makes the world seem soft and they can no longer work on my metal body, they lay side by side on the floor and watch the sharp smoke dance on the ceiling.

t night, when their spines are stiff and their vision makes the world seem soft and they can no longer work on my metal body, they lay side by side on the floor and watch the sharp smoke dance on the ceiling.

“He is with the angels,” the father says.

“If he is with the angels, then the angels are thieves,” the mother says. The smoke on the ceiling catches the light and traps it. I am in the smoke and I am in the light.

“Is there something wrong with us?” the father asks. Every part of him aches. His hands feel raw and burned at the edges, and his mind is a glowing coal.

“Yes,” the mother says. She feels the insides of herself sliding loose daily like pieces of ice in a sea. She seems to have lost track of her heart. Perhaps it has shattered, and she cannot locate it when she tries nor sync it with the few clients that still come to their shop in the day. “There is something wrong with us.”

“Hold my hand,” the father says. The mother places her hand in his. Both think the other is unnaturally cold, like metal.

They sleep in the way of the dead. Absolutely motionless, and without dreams.

am not their son. I am humanity’s dream. I am the ghost they do not expect. I watch them from between strands of sunlight and from behind the stars. I watch them sleep.

am not their son. I am humanity’s dream. I am the ghost they do not expect. I watch them from between strands of sunlight and from behind the stars. I watch them sleep.

They so hope I am their son, but a soul is an accretion. Their child’s soul was so delicate and small as it crept out of his body. A tiny bird or butterfly of light floating and unraveling into the ether. Light, and very faintly cool.

His crib was made of rosewood. The father had carved it himself and stained it a dark red. He had carved wings into the side to carry the boy, in his sleep, to a higher place.

The mother wears her guilt like a fine dress. She handles it cautiously as if concerned she might tear or damage it. She believes there is a flaw somewhere in the anatomy of her body, which she must never allow herself to forget.

The father does not blame her. He considers himself a man of science and of action. Remorse, he tells himself, is without utility. His guilt is closer to bone, hard and primal and buried somewhere deep beneath his skin.

Their child was beautiful in the way of all new, innocent things. Potential rising off its skin like the scent of unformed clay. He had bright, curious eyes that never seemed to close. He had perfect hands with which he grasped his father’s fingers and beard and his mother’s long curls.

After his death, the mother cut her hair very short and wild, and the father shaved off his beard with a hunting knife.

The boy spoke in babel, which sounded, to them, like a kind of spell or lost alchemic incantation.

“He will be a great man of science. He will change the world,” the father said.

The mother laughed and said to the child, “Don’t listen to your silly father. Become whatever you wish to become.”

Perhaps his lungs were too small, or his little heart could not hold the world. He died in his crib, and a stillness and silence radiated out from him like the dark light of a candle.

The child’s soul, so fragile and new, would have been torn apart in the wind or in the harsh light of the sun if I had not eaten it. It came apart in my teeth and dissolved like spun sugar.

Children’s souls are sweetest, and most fleeting on my tongue.

am the accretion of many dark dreams. I am the crowd of lost souls. I am God’s shadow. I know the old magic that made the moon. I speak the secret language of the stars and the sun. I speak with the fire. I was born out of the dark minds of men and the iron blood of women. My heart is stone. My veins are metal. Demon, they call me. Demon. I have watched cities burn and I have raised them. I have been summoned to make cities burn. I have eaten thousands of souls and I have taken so many lives in payment for so many sins.

am the accretion of many dark dreams. I am the crowd of lost souls. I am God’s shadow. I know the old magic that made the moon. I speak the secret language of the stars and the sun. I speak with the fire. I was born out of the dark minds of men and the iron blood of women. My heart is stone. My veins are metal. Demon, they call me. Demon. I have watched cities burn and I have raised them. I have been summoned to make cities burn. I have eaten thousands of souls and I have taken so many lives in payment for so many sins.

When I have a body, I wonder what souls will taste like then. And when I hold the world in my metal hands, how fragile it will seem.

here is lightning like the thoughts of God. Jagged and brief and blinding. Raindrops shatter on the windows. My body sings. I look like a patchwork skeleton filled with gears and glass. Slightly taller than a man, but with huge, complicated hands. They wanted me to be able to hold things. All my other joints are simple. The wooden apparatus in the corner of their lab that kept my empty body upright is charred and blackened from the lightning recently channeled down into it from the iron rod on their roof. It smells sweet to me, almost like burning fruit, and the smell has a body and a depth to it that that shocks me.

here is lightning like the thoughts of God. Jagged and brief and blinding. Raindrops shatter on the windows. My body sings. I look like a patchwork skeleton filled with gears and glass. Slightly taller than a man, but with huge, complicated hands. They wanted me to be able to hold things. All my other joints are simple. The wooden apparatus in the corner of their lab that kept my empty body upright is charred and blackened from the lightning recently channeled down into it from the iron rod on their roof. It smells sweet to me, almost like burning fruit, and the smell has a body and a depth to it that that shocks me.

It’s physical, and it makes my soul quiver.

The mother is holding her chest, as if trying to press down her heart. As if her heart is the one that’s beating for the very first time. Her hair is greasy and her skin shines with sweat. Now that I am so close to it, her humanity disgusts me.

I feel powerful beyond belief. The universe in my chest. I could make this city vanish with a single beat of my heart.

The father is weeping. Fat human tears that make rainbows out of the firelight too small for either of them to see. I can smell his soul, like good wood to be burned. This sensation is new and it excites me. The mother takes a tentative step forward. The father reaches out his hand. It is swollen and burned and stained with grease from all his work. It is shaking. The mother’s face is filled with such brittle hope. They would so like me to be their son. There is a sense in them, I feel it, of the world ending.

All their hopes are in the air, as insubstantial as smoke.

The father is still offering his hand to me, and, surprising myself, I reach out mine in return. Greased gears sing and grind together. Lightning cries outside a window and throws grotesque shadows at our feet. My heart beats eternity in my metal chest. My hand is so large that the father’s hand disappears inside of it. It’s as if he is the son, the child, seeking reassurance from his father that the world is indeed a safe place.

They have cared for me, in a way.

“You must be frightened,” the mother says. The strings of her heart are coming loose in her chest. I can feel it. “Don’t worry, my child. This time, we’ll protect you. I swear.”

The father nods and wipes at his eyes.

“You’re safe, my son. I promise,” he says, and it is like the words are collapsing out of him.

How easily I could crush this hand. The entire world feels frail beneath my copper feet. I can sense souls all across the globe, blinking like stars. Fat and sweet like exotic fruits just about to fall from their trees. But I hold his hand carefully, conscious of all his little bones.

Some of the father’s tears have rolled onto his lip and they hang there in his stubble like jewels. And I have the strange urge to reach out and wipe them away with a metal finger. Where do these feelings come from?

Ryan Row lives in Oakland, California, with a beautiful and mysterious woman. His short fiction has appeared, or is forthcoming, in Quarterly West, Shimmer, Bayou Magazine, Clarksworld, and elsewhere. He is a winner of The Writers of the Future Award and holds a B.A. in Creative Writing from San Francisco State University. You can find him online at ryanrow.com